|

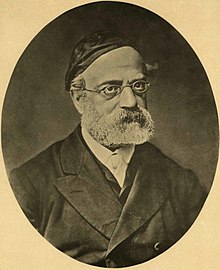

| The late Lubavitcher Rebbe, R' Menachem Mendel Schneersohn |

A short while ago, a Chabad website

featured a letter (written in 1962) from the late Lubavitcher Rebbe,

R' Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. Therein he essentially trashed Rav Samson

Rapahel Hirsch's seminal philosophy of Torah Im Derech Eretz (TIDE) - calling

it irrelevant if not destructive in our (his) day.

The Avner Institute presents a 1962 letter from the Rebbe

to a Yeshiva University professor about the nature of today’s American Jewish

youth and why they can no longer relate to Rabbi Samson Rafael Hirsch's

philosophy of "Torah im Derech Eretz, where the Torah is maximized in

partnership with worldly involvement."

|

| TIDE founder, R' Samson Raphael Hirsch |

Rabbi Hirsch has been considered controversial among many

prominent rabbis, who disapproved of his integration of secular and Jewish

studies. Nevertheless, there are some who understand “Derech Eretz” to mean

anything elevated through Torah study or practice, and therefore secular

studies can be reconciled with practical knowledge or whatever was necessary to

earn a living.

Other Jews, however, understand Rabbi Hirsch in the sense

of Torah U’Madda, (TuM) a synthesis of Torah knowledge and secular

knowledge–each for its own sake. This is the prevalent philosophy of Yeshiva

University, the New York campus noted for its blended curricula. In this view,

it is considered permissible, and even productive, for Jews to learn gentile

philosophy, music, art, literature and ethics for their own sake.

The following is a letter of the Rebbe. Written in 1962

to a Yeshiva University professor, the Rebbe explains the nature of today’s

American Jewish youth and why they can no longer relate to Rabbi Hirsch’s

philosophy of Torah im Derech Eretz.

My reactions to the Rebbe’s perspectives are interspersed

below, in bold.

I must touch upon another, and even more delicate, matter

concerning the teachings of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch whom you mentioned in

your letter.

There has been a tendency lately to apply his approach in

totality, here and now in the United States. While it is understandable that

the direct descendants of Rabbi Hirsch or those who were brought up in that

philosophy should want to disseminate his teachings, I must say emphatically

that to apply his approach to the American scene will not serve the interests

of Orthodoxy in America. With all due respect to his philosophy and approach,

which were very forceful and effective in his time and in his milieu, Rabbi

Hirsch wrote for an audience and youth which was brought up on philosophical

studies, and which was permeated with all sorts of doctrines and schools of

thought and disciplined in the art of intellectual research etc. Thus it was

necessary to enter into long philosophical discussions to point out the fallacy

of each and every thought and theory which is incompatible with the Torah and

mitzvoth. There was no harm in using this approach, inasmuch as the harm had

already been there, and if it could strengthen Jewish thought and practice, it

was useful, and to that extent, effective.

What the Rebbe is saying here applies with no doubt to

many of RSRH’s works. But TIDE is a philosophy that transcends the writings of

RSRH that no longer appeal in style and approach to today’s seekers. As I wrote

in a footnote to my “Forks in the Road” article about Chassidus and Misnagdus:

A detailed treatment of Rabbi

Samson Raphael Hirsch’s philosophy as reflected in the writings of his

grandson, Dr. Isaac Breuer, is presented in my essay: Dr. Yitzchok Breuer

zt"l and World History. I believe it is accurate to state the following

distinction: The schools of thought presented here focus on the Avodas Hashem

that is the predominant aspect of life. Torah im Derech Eretz, on the other

hand, focuses on the totality of life — of a person, of the nation, and of the

world —and living that life in a manner consistent with what Torah im Derech

Eretz understands to be Hashem’s will and purpose for the person, the nation

and the world. Hence, it is entirely possible to not follow Rabbi Hirsch’s

system of Avodas Hashem (as presented in Chorev and other works),

following, instead, other approaches to Avodas Hashem, such as those presented

here, and still be an adherent, on the more global or holistic level, of Torah

im Derech Eretz. (Conversely, it is theoretically possible for someone to reject

Torah im Derech Eretz yet adopt a Hirschian mode of Avodas Hashem.)

The Rebbe continues:

However, here in the United States we have a different

audience and a youth which radically differs from the type whom Rabbi Hirsch

had addressed originally. American youth is not the philosophic turn of mind.

They have neither the patience nor the training to delve into long

philosophical discussions, and to evaluate different systems and theories when

they are introduced to all sorts of ideas, including those that are

diametrically opposed to the Torah and mitzvoth, and there are many of them,

since there are many falsehoods but only one truth, this approach can only

bring them to a greater measure of confusion. Whether or not the final analysis

and conclusions will be accepted by them, one thing is certain: that the seeds

of doubt will have multiplied in their minds, since each theory has its

prominent proponent bearing impressive titles of professors, PhDs, etc.

Here is where the Rebbe conflates TIDE with Torah u’Madda.

The adherents of TIDE present secular perspectives as subordinate, yet

essential, enhancements of Torah itself. It is TuM, especially in RYBS’s (R’Yosef Ber Soloveitchik) Ramasayim

Tzofim perspective, that does not automatically clarify that secular

perspectives are, perforce, subordinate to Torah and only validated thereby.

The Rebbe here is, to a very large extent, adhering to

classic Chassidic perspectives that associate Chochmos Chitzonyios with kelipos.

And not with kelipas noga…

This is very much counter to the Misnagdic perspective of

the Gra, which is almost identical to TIDE. The following abridgment of the

famous passage in the Introduction to the Pe’as HaShulchan is at https://avodah.aishdas.narkive.com/xnxeZiVR/the-vilna-gaon-and-secular-wisdom:

The following is from pages 148-149 of Judaism's

Encounter with

Other Cultures: Rejection or Integration?

Given what the GRA said below, one can only wonder why

music is not

taught in all of our yeshivas. For the record, a friend

of mine who

is the secular studies principal of a Mesivta in Brooklyn

wrote to

me that his school does have a course in music

appreciation. YL

R. Israel of Shklov (d. 1839) wrote:

I cannot refrain from repeating a true and astonishing

story that I

heard from the Gaon's disciple R. Menahem Mendel. It took

place when

the Gaon of Vilna celebrated the completion of his

commentary on Song

of Songs... He raised his eyes toward heaven and with

great

devotion began blessing and thanking God for endowing him

with the

ability to comprehend the light of the entire Torah. This

included

its inner and outer manifestations. He explained: All

secular wisdom

is essential for our holy Torah and is included in it. He

indicated

that he had mastered all the branches of secular wisdom,

including

algebra, trigonometry, geometry, and music. He especially

praised

music, explaining that most of the Torah accents, the

secrets of the

Levitical songs, and the secrets of the Tikkunei Zohar

could not be

comprehended without mastering it... He explained the

significance

of the various secular disciplines, and noted that he had

mastered

them all. Regarding the discipline of medicine, he stated

that he

had mastered anatomy, but not pharmacology. Indeed, he

had wanted to

study pharmacology with practicing physicians, but his

father

prevented him from undertaking its study, fearing that

upon

mastering it he would be forced to curtail his Torah

study whenever

it would become necessary for him to save a life... He

also

stated that he had mastered all of philosophy, but that

he had

derived only two matters of significance from his study

of it...

The rest of it, he said, should be discarded." [11]

[11.] Pe'at ha-Shulhan, ed. Abraham M. Luncz

(Jerusalem, 1911), 5a.

This translation

actually excludes a key line, and misses a key line elsewhere in the Talmidei

HaGra – see https://www.yeshiva.org.il/wiki/index.php?title'רבי_אליהו_מוילנא:

דעת הגר"א על לימוד חכמות החול

תלמידי הגר"א מעידים שהגר"א ראה חשיבות וערך

בלימוד חכמות החול. רבי ישראל משקלוב, תלמיד הגר"א, מביא (בהקדמתו ל'פאת

השולחן', ד"ה ומצידה ביאור ארוך; - מובא להלן בהרחבה) בשם רבו

כל החכמות נצרכים לתורתנו הקדושה[31]

וכלולים בה[32]

דברים דומים, אך חדים וחריפים יותר, נוכל למצוא בהקדמה לספר

"אוקלידוס" המתורגם לעברית על ידי רבי ברוך (בן יעקב) שיק משקלוב, (האג

תק"ם), בה מספר המתרגם[33]

"והנה בהיותי בק"ק (- קהילת קודש) וילנה

המעטירה, אצל הרב אצל הרב המאור הגאון הגדול מ"ו (- מורנו ורבנו) מאור עיני

הגולה החסיד המפורסם כמוה"ר אלי' נר"ו (- הגר"א), בחודש טבת תקל"ח,

שמעתי מפיו

כי כפי מה שיחסר לאדם ידיעות משארי החכמות — לעומת זה יחסר לו מאה

ידות בחכמת התורה, כי התורה והחכמה נצמדים יחד

וצִווה לי (- הגר"א) להעתיק מה שאפשר ללשוננו הקדוש

מחכמות [החול][34], כדי להוציא בולעם

מפיהם[35] וישוטטו רבים ותרבה הדעת[36] בין עמנו ישראל

The Rebbe continues:

Besides, the essential point and approach is “Thou shalt be

wholehearted with G-d, thy G-d.” The surest way of remaining a faithful Jew is

not through philosophy but through the actual experience of the Jewish way of

life in the daily life, fully and wholeheartedly. As for the principle “know

what to answer the heretic,” this is surely only one particular aspect, and

certainly does not apply to everyone. Why introduce every Jewish boy and girl

to the various heretics that ever lived?

This, too, is a straw-man argument. Indeed, the approach

of RSRH is much less about philosophy and certainly not about heresy. The

following controversy does exist, but is not at all in line with the Rebbe’s

assertion. I have written elsewhere:

Of course, not everyone may agree

with Prof. Levi's perspective (that Hirschian TIDE is expressed in the study of

mathematics and the sciences, not in the study of secular literature). In a

recent essay published in Judaism's Encounter with Other Cultures: Rejection

or Integration?, Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Har

Etzion takes a very different view (see also Avodah Mailing List 3:107 at www.aishdas.org).

In his essay, Torah and

General Culture: Confluence and Conflict, Rabbi Lichtenstein argues that

the madda that complements Torah includes the humanities as well:

And yet at bottom, the notion

that Shakespeare is less meaningful than Boyle, Racine irrelevant but Lavoisier

invaluable, remains very strange doctrine indeed. Rabbi Lichtenstein writes:

To those who extol chemistry

because it bespeaks the glory of the Ribbono Shel Olam but dismiss

Shakespeare because he only ushers us into the Globe Theater, one must answer,

first, that great literature often offers us a truer and richer view of the

essence – the Inscape, to use Hopkins' word – of even physical reality… Can

anyone doubt that appreciation of God's flora is enhanced by Wordsworth's

description of: A crowd/ a host, of golden daffodils;/ Beside the lake, beneath

the trees,/ Fluttering and dancing in the breeze?

Rabbi Lichtenstein continues to

assert:

Whether impelled by demonic

force or incandescent aspiration, great literature, from the fairy tale to the

epic, plumbs uncharted existential and experiential depths which are both its

wellsprings and its subjects… Hence, far from diverting attention from the

contemplation of God's majestic cosmos, the study of great literature focuses

upon a manifestation, albeit indirect, of His wondrous creation at its apex… To

the extent that the humanities focus upon man, they deal not only with a

segment of divine creation, but with its pinnacle… In reading great writers, we

can confront the human spirit doubly, as creation and as creator.

But

how does this approach complement Torah?

The dignity of man is not the

exclusive legacy of Cicero and Pico della Mirandola. It is a central theme in

Jewish thought, past and present. Deeply rooted in Scripture, copiously

asserted by Chazal, unequivocally assumed by Rishonim, religious

humanism is a primary and persistent mark of a Torah weltanschauung.

Man's inherent dignity and sanctity, so radically asserted through the concept

of Tzelem Elokim; his hegemony and stewardship with respect to nature,

concern for his spiritual and physical well-being; faith in his metaphysical

freedom and potential – all are cardinal components of traditional Jewish

thought… How then can one question the value of precisely those fields which

are directly concerned with probing humanity?

But cannot sources for religious inspiration be found in

Torah?

An account of Rabbi Akiva's

spiritual odyssey could no doubt eclipse Augustine's. But his confessions have

been discreetly muted. The rigors of John Stuart Mill’s education – and

possibly, their repercussions – are not without parallel in our history. But

what corresponds to his fascinating Autobiography? Or to the passionate Apologia

Vita Sue of his contemporary, John Henry Cardinal Newman? Our Johnsons have

no Boswells.

To be sure, Rabbi Lichtenstein's

arguments are impassioned and eloquent. I cannot speak for Prof. Levi, but I

imagine that he would argue that in the absence of solid and conclusive

evidence from Chazal and other classic sources, Rabbi Lichtenstein's

position cannot be considered normative.

It is well beyond the scope of

this review to contrast Rabbi Lichtenstein… with Prof. Levi… It is tantalizing

to reflect on the different statements with which they approach the gap between

the perspectives they champion and the dominant Torah-only school.

Rabbi Lichtenstein:

Advocates of Torah u-Madda can

certainly stake no exclusive claims. It would not only be impudent but foolish

to impugn a course which has produced most Gedolei Yisrael and has in

turn been championed by them. Neither, however, should exclusionary contentions

be made by its opponents. While Torah u-Madda is not every one's cup of tea, it

certainly deserves a place as part of our collective spiritual fare.

Prof. Levi (p. 251):

I cannot conclude without

addressing the sharp contrast between what we have learned here, concerning the

centrality of the Torah Im Derech Eretz principle, and what we see in the

yeshiva world… I have heard from several great Torah scholars that this

opposition is a temporary injunction (hora'ath sha'ah). In time of

emergency, it is indeed sometimes necessary to deviate from the Torah's demands

in order to save the Torah itself… This was especially important after the

terrible Holocaust that visited European Jewry.

To Rabbi Lichtenstein, his approach is an available

option. Prof. Levi, on the other hand, sees his approach as normative. To me,

Rabbi Lichtenstein’s approach is only an option because he subscribes to

his illustrious father in law’s Ramasayim Tzofim perspective of TuM. In

my opinion, RSRH, on the other hand, would see Rabbi Lichtenstein’s approach as

modified by TIDE as normative. After all, RSRH was an admirer of Friedrich von

Schiller (see https://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/745805/professor-marc-b-shapiro/07-rabbi-samson-raphael-hirsch-and-friedrich-von-schiller/).

The Lord of the Rings has its place in Hirschian TIDE, although perhaps not

in the TIDE of the Gra.

The Rebbe continues:

The whole problem is a delicate one, and I have written the

above only in the hope that you may be able to use your influence with certain

circles in Washington Heights, that they should again re-examine the whole

question and see if the Rabbi Hirsch approach should be applied to the American

scene. My decided opinion is, of course, that it should not, and I hope that

whatever measure of restraint you may accomplish through your influence will be

all good. I hope to hear good news from you also in regard to this.

I don’t know to which side of Washington Heights the

Rebbe was referring, but I believe he would have received strong-worded

rejections from both the east (Yeshiva University) and west (Hirshean) sides of the Heights.

The Rebbe continues:

Enclosed is a copy of my message to the delegates of N’shei

Chabad, which I trust Mrs. Goodman will find interesting, since the contents of

the message are intended for all Jewish men and women.

I was gratified to read in your letter that you recall our

conversation with regard to your writing of your memoirs, and, as in case of

all recollections in Jewish life, the purpose of which is to give it expression

in actual deed, I trust that this will be the case also in regard to your

memoirs.

I want to take this opportunity to mention another point

which we touched upon during our conversation, and which I followed up in

writing. I refer to the movement of Torah im Derech Eretz, which has sometimes

become a doctrine of Derech Eretz im Torah, alluding to the saying of our Sages

that derech eretz came before Torah. However, the term derech eretz is

interpreted as a college education, and it is claimed to be the doctrine of

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch of blessed memory.

This is such a simplistic understanding of TIDE that it

is staggering to me that the Rebbe could have written such a distorted statement.

Rabbi Joseph Breuer, A Unique Perspective, pp. 387-388:

Generally, the superficial

student deduces from the TIDE precept… the necessity of acquiring secular

knowledge, i.e., the training and proficiency in worldly cultures and

professions…

...in a broader sense, Derech

Eretz embraces the “earth way” of a Yehudi, who seeks self perfection in

all his actions and strivings under the rulership of the Will of God.

The Rebbe continues:

As you will recall, I made the point in my previous letter

on this subject that in my opinion, with all due respect to this policy and

school of thought which had their time and place, they are not at all suitable

for American Jewish youth and present times and conditions, especially in the

United States. I even made so bold a move as to try to enlist your cooperation

to use your influence to discourage the reintroduction of this movement on the

American Jewish scene, since it is my belief that your word carries a great

deal of weight in these circles here.

I want to note with gratification that on the basis of

unofficial and behind the scenes information which has reached me from the

circles in question, the point which I made with regard to this school of

thought has been gaining evermore adherents. It is becoming increasingly

recognized that a college education is not a vital necessity and is not even of

secondary importance. Many begin to recognize that the Torah, Toras Chaim,

is, after all, the best sechorah (reward), even as a “career.” In the

light of this new reappraisal, attendance at college is being recognized as

something negative and interfering with detracting from the study of Torah. So

much for the younger generation.

Again, the simplistic, reductionist understanding of

TIDE.

The Rebbe continues:

However, the older generation, especially those, whose own

character and background has been fashioned overseas, in Germany, still cling

to the said school of thought. The reason may be because it is difficult for a

person in the prime of his life, or in a more advanced age, to radically change

his whole outlook and reexamine the whole approach in which one has been

trained and steeped, in the light of contemporary conditions in the United

States, or it may simply be due to inertia and the like.

In view of the above, and inasmuch as a considerable impact

has already been made in the right direction, I consider it even more

auspicious at the time that you should use your good influence in this

direction. All the more so since, judging by your energy and outlook, I trust

you can be included with the younger generation and not the older one. For the

younger generation is not only more energetic and enthusiastic about things,

but is more prone to take up new ideas which require an extra measure of

courage, to be different from others and to face new challenges. I believe that

you have been blessed with a goodly measure of these youthful qualities.

It is indeed a tragedy that the younger generation did

not receive education in precepts of TIDE. Every time a Jew alleged to be

Torah-true gets caught in fraudulent and deceptive dealings the tragedy is

manifest. Rabbi Breuer penetrating aphorism concerning Glatt Yosher

comes to mind. As he writes (ibid., p. 369):

God’s Torah not only demands the

observance of kashrus and the sanctification of our physical enjoyment; it also

insists on the sanctification of our social relationships. This requires the

strict application of the tenets of justice and righteousness, which avoids

even the slightest trace of dishonesty (emphasis in the original) in our

business dealings and personal life.

I might conclude that this subject is timely in these days,

on the Eve of Shavuot when the first condition of receiving the Torah was the

unity of the Jewish people so that it could be receptive to the unity of G-d,

as expressed in the first and second of the Ten Commandments. For the unity of

G-d means not only in the literal sense of the said commandments, but that

there should be no other authority or power compared with G-dliness, until there

is the full realization that “There is nothing besides him.” And this idea is

brought about by the One Torah, which is likewise one and only and exclusive,

so that when we say that it is Toras Chaim, it means that it is

literally our very source and only source of life in this life, too, and that

there can be no other essential source or even a secondary source next to the

Torah, even as far as our daily resources in the ordinary aspects of the life

are concerned.

And we conclude with the words of Rabbi Breuer (ibid.,

pp. 534, 536):

RSRH, together with his

contemporary rabbinic leaders considered TIDE, as he enunciated it, a

necessity, and declared emphatically that it was not a הוראת שעה. His

eminent successor, Rav Dr. Salomon Breuer, said just shortly before his passing

that he was convinced that this approach “will be מקרב הגאולה…"

...The TIDE approach is the right one for ארץ ישראל and

the Disapora. The waves that rush over the TIDE approach at the present time

will run out and they will also take their victims with them. As we have

stated, the TIDE approach must unfortunately expect to suffer losses, with its

demand of perseverance and dedication to Torah. This will be true until the

time of Moshiach, when the Prophetic promise (Yeshayahu 60:21) ועמך כולם צדיקים will be realized, במהרה בימינו.